Of the few permanent structures that opened

in Flushing Meadow in April 1964, the one that was intended as

the greatest long-term legacy lay just outside the Fair's Main

Entrance, across a walkway and parking lot: Shea Stadium, the

brand new home of both the New York Mets baseball team

and New York Jets (formerly Titans) AFL football

team.

It was only coincidence caused by construction

delays that saw Shea Stadium open at the same time the World's

Fair did. The original planning had called for it to be ready

the previous season (the Mets had even held a farewell

to the Polo Grounds ceremony at the end of the 1962 season and

then were forced to do it again at the end of 1963). In many

ways the timing worked out perfectly as it allowed Shea to stand

out as part of the aura of dynamic Space Age progress that the

Fair symbolized. Shea Stadium was the first new stadium for New

Yorkers in more than 40 years and it epitomized all the things

that Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field were not.

At Shea a spectator could finally, for

the first time, not have to worry about getting a seat with an

obstructed view caused by a support post, that for all ballparks

built before the 1950s was a necessary evil in order to accommodate

a multi-level facility. At Shea a suburban visitor could make

use of an ocean of available parking space for his car, something

that wasn't available at Yankee Stadium or either of the bygone

ballparks. And at Shea a visitor from the more upscale suburban

communities could see a game without the uneasy feeling that

he had put his safety at risk by coming to a game in a deteriorating

neighborhood.

Yankee Stadium, Ebbets Field and the Polo

Grounds had all been built in the early decades of the 20th Century

in what had been middle-class urban neighborhoods with thriving

homes and businesses surrounding the ballpark environs. The Concourse

Plaza Hotel, located just beyond Yankee Stadium, was regarded

as a luxury hotel and served as the in-season home for most of

the ballplayers. But by the 1950s these once middle-class communities

were spiraling into a state of decay and neglect caused largely

by the changing demographics of post-World War II America. The

great highways of the future predicted by the original New York

World's Fair of 1939 had brought with them an exodus of the middle-class

from traditional urban neighborhoods to new homes in the emerging

suburbs that enabled a person to live in more quiet, pastoral

settings while still working in the city. The departure of the

middle-class meant that those from the lower classes inevitably

moved into the abandoned neighborhoods. In the space of two decades

urban decay had settled in, with a marked increase in crime in

the very neighborhoods that housed New York's three venerable

ballparks.

Despite the fact that from 1947-1956, all

three teams were dominating baseball like never before (the Yankees

won eight pennants and seven championships in that span, the

Dodgers six pennants and a championship, and the Giants two pennants

and a championship), attendance seldom rose above more than one

and a quarter million for any of the New York teams after 1950.

Inevitably, the blame was fixed on the deteriorating neighborhoods,

which to a suburban fan took on added weight since he could now

stay at home and watch a game on television without having to

travel to a run-down community. Ultimately, for the Brooklyn

Dodgers and New York Giants, their belief that New York would

never build a new stadium in a better neighborhood that could

draw more fans led them to abandon New York for the untested

regions of California after the 1957 season.

New York tried its best to convince the

Dodgers, at least, that they could get a new ballpark that, while

not situated in Brooklyn itself, would be located close enough

to their natural fan base to allow for suburban fans from Long

Island to make the trip with a greater sense of security. New

York's Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had long viewed the construction

of a stadium in Flushing Meadow as one of the keys toward achieving

the rehabilitation of the site that had not taken place after

the closing of the 1939-40 World's Fair. On April 10, 1957, he

put forth a proposal to Dodger owner Walter O'Malley that called

for $12 million of city funds for a new facility in Flushing

Meadow that would satisfy the Dodgers needs for larger seating

(Ebbets Field was a bandbox in size, seating no more than 35,000

which often meant smaller revenue streams during the many World

Series the Dodgers participated in during the 1950s), safe parking

away from any deteriorating neighborhood and access to a public

transportation line that could bring fans to the stadium by subway.

O'Malley, however, was never interested

in Flushing Meadow as a site for a new ballpark. His obsession

centered on a piece of land at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush

Avenues in Brooklyn where he wanted to build a large domed stadium

out of his own pocket. He needed to get the city to turn over

the land to him and on this, both New York mayor Robert Wagner

and Robert Moses, the two allies O'Malley needed, adamantly refused

since it would have meant removing land from the city's tax rolls

for O'Malley's use and would have put O'Malley in position to

reap the rewards of development in the area immediately adjacent

to the new ballpark. Irving Rudd, who worked for the Dodgers

during this time as promotions director, later put it succinctly

to author Peter Golenbock "If they had given O'Malley what

he wanted, they should have gone to jail."

Oddly, there is no indication that Moses

and Wagner ever thought of using Flushing Meadow as an opportunity

to keep the Giants in New York once it was clear that O'Malley

wasn't going to move the Dodgers to Queens (In rejecting the

proposal, O'Malley said that if the Dodgers moved out of Brooklyn,

even to Queens, it would be no different than moving to California.

Many Brooklyn fans would certainly have taken exception to that).

By that point Giants owner Horace Stoneham was so determined

to leave New York (where he had real financial problems) that

no doubt Moses and Wagner realized it would have been a futile

gesture.

And so when the 1958 baseball season opened

New York suddenly found itself reduced from three baseball teams

to one. Almost immediately there was a clamor from city officials

to get baseball to bring a National League team back to New York

since it was clear that the deprived Dodger and Giant fans would

not be swallowing their pride to become Yankee fans. But since

no National League team was interested in relocating to New York

and because there had never been an expansion of the league in

the 20th Century, it seemed that such appeals would forever fall

on deaf ears. What finally got Major League Baseball to do an

about-face and bring the National League back to New York was

the sudden threat of an independent third league forcing its

way into the big time.

The proposed Continental League was the

brainchild of New York attorney Bill Shea who, after failing

to convince an established National League team to move to New

York, decided to take action by organizing a proposed third league

with franchises based in New York, Houston, Denver, Toronto and

other cities without a Major League team. It was Shea who found

a solid financial backer for the proposed New York franchise

in Joan Whitney Payson, a former Giants minority stockholder.

And with the presence of former Dodger General Manager Branch

Rickey as President of the proposed league, it was clear that

this endeavor was determined to succeed. Both the American and

National League decided it would be easier to compromise and

accommodate some of the proposed Continental franchises through

an expansion of both leagues in 1961 and 1962. New York would

be added to the National League under the formula starting in

1962.

Once New York had been approved, Mayor

Wagner and Robert Moses wasted little time in dusting off the

Flushing Meadow proposal for the new stadium that Walter O'Malley

had rejected. By this point, Moses was already beginning his

preparations for the overall rehabilitation of Flushing Meadow

by a new World's Fair and the opportunity to further improve

the park's long-term health with a stadium could only be a godsend.

The New York legislature passed a bond measure that would pay

for the construction costs and, on October 6, 1961, the new team,

officially called the "Metropolitans" but from the

outset referred to as "Mets", signed a 30 year lease

to play in the new stadium. Not long afterwards the American

Football League's New York Titans, which had come into existence

with the renegade football league in 1960 and played their games

in the Polo Grounds, signed on to play in the new stadium as

well. The Flushing Meadow stadium would now have almost total

year-round use.

The decision was made to name the new stadium

in honor of Bill Shea recognizing that without his efforts to

propose the Continental League, New York would never have received

a second team again and the stadium would not exist. It was a

very rare case where a new stadium's name was not tied to either

location (such as San Francisco's Candlestick Park), a club owner

or executive (Ebbets Field had been named for the Dodgers then-owner

when it opened in 1912), or the team itself (Yankee Stadium).

For many years afterwards Mets fans entered Shea Stadium with

little idea of the man who the stadium had been named for. In

a Mets team history video in 1985, Bill Shea chuckled as he recalled

one occasion when he visited the ballpark not long after it opened,

"There were two fans in front of me and one of them was

asking, 'Who the heck was that guy Shea they named the place

after?' And the other guy said, 'Oh, he was a ballplayer that

was killed in the First World War.'"

If there was anyone else who could have

conceivably earned the right to have the stadium named after

him, it would have been Robert Moses. The Flushing Meadow site

had been his brainchild as part of his overall vision to see

Flushing Meadow Park transformed into a "super urban park,"

providing more convenience to the increasingly suburban tilt

of New York's population that was moving eastward into Long Island.

Once it was clear that National League baseball would be returning

to New York, no thought was given to any other location than

Moses'. And because Shea's opening would ultimately coincide

with the 1964 World's Fair that was, unrealistically, expected

to attract 70 million visitors, it seemed only natural to think

that building Shea in the same location would help enhance Fair

attendance.

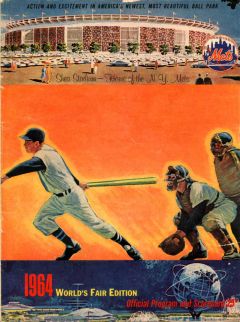

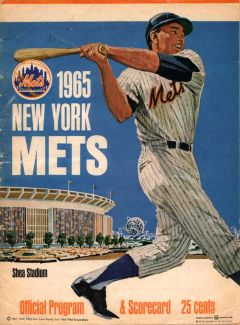

Official Met's Program and Scorecard

for the 1964 (l.) and 1965 (r.) Seasons. The Fair and Shea Stadium

were in each other's best interests in '64 and '65.

|

|

|

|

We can never know for certain how many

visitors to Shea that first year also took advantage of the Fair's

proximity. But in that first season of 1964 the Mets drew 1.7

million in attendance, nearly doubling the numbers they had drawn

to the decaying Polo Grounds in 1962 and 1963. The new locale

didn't improve their inept playing but for the first time the

Mets began to look like the team of the future which fit in nicely

with the theme of the "Space Age" World's Fair. 1964

saw the emergence of their first homegrown player, second baseman

Ron Hunt, who was elected to the 1964 All Star Game (played at

Shea, and won by the NL on a dramatic game ending home run by

Johnny Callison of the Phillies), while the following year saw

outfielder Ron Swoboda, later a key member of the 1969 "Miracle

Mets" championship team, burst on the scene and set a rookie

record for home runs in a month.

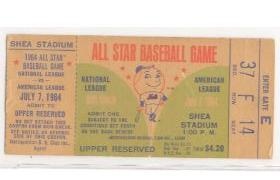

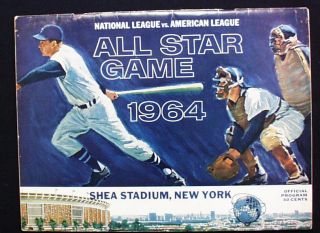

1964 All Star Game ticket and

Souvenir Program

|

LISTEN ! - From the original NBC

Radio broadcast: Philadelphia's Johnny Callison hits a game-ending

home run to win the 1964 All Star Game at Shea Stadium for the

National League, 7-4. (Blaine Walsh, announcer). LISTEN ! - From the original NBC

Radio broadcast: Philadelphia's Johnny Callison hits a game-ending

home run to win the 1964 All Star Game at Shea Stadium for the

National League, 7-4. (Blaine Walsh, announcer).

|

By contrast, the mighty Yankees dynasty

that had won fifteen American League pennants in eighteen years

since 1947 was beginning to crumble. In 1964 the Bronx Bombers

of Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and Whitey Ford had to rally from

far back to win one last pennant before bowing out to the St.

Louis Cardinals in the World Series. The next year, age and injury

set in at once and the Yankees collapsed to sixth place, followed

by a last place finish in 1966. During the second year of the

Fair, New Yorkers now had a choice between an aged declining

team playing in an increasingly dated facility in a bad neighborhood

and a team that, while losing, was injecting more and more youth

into the mix and playing in a comfortable modern facility. It

was no contest and the Mets finally became the undisputed focal

point of baseball in New York -- a status they would enjoy through

their championship in 1969 and well into the 1970s before bad

ownership decisions and the dawn of free agency sent them in

a tailspin while the simultaneous rebirth of the Yankees

in a modernized Yankee Stadium in 1976 shifted the focus back

to the Bronx Bombers as New York's premier team.

Today, nearly forty years after it first

opened as the symbol of what the "Space Age" World's

Fair was all about, Shea Stadium is the third oldest National

League ballpark still in use trailing only Chicago's venerable

Wrigley Field and Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles (which opened

in 1962). The impulse to build stadiums away from urban neighborhoods

and in more outlying communities has long since passed with the

emphasis now on building smaller "classic" style ballparks

in downtown urban locations in the hope that they will bring

a larger economic and cultural revitalization of the community.

In effect, the vision that Walter O'Malley wanted to prevail

in his Atlantic Avenue site for a ballpark in Brooklyn has now

come to pass in such cities as Baltimore, Cleveland and Denver.

By contrast, Shea Stadium, situated in a sea of parking lots

across from a park that after the Fair's closing still failed

to fully live up to what Robert Moses had envisioned, has become

the kind of quaint relic from the past that Yankee Stadium, the

Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field seemed in 1964. Several repaintings,

and the partial enclosure of the outfield caused by two giant

"Diamond Vision" screens, have only served as cosmetic

attempts to conceal its age. The departure of the New York Jets

football team for the New Jersey Meadowlands in 1984 further

underscored Shea's inability to maintain the aura of up-to-date

sophistication it projected during its first two years when the

Fair was in full swing.

Today, when visitors come to Shea, they

do so in general ignorance of why the stadium is so-named. And

even if they look beyond the parking lots and see the nearby

Unisphere they might not fully recognize how both structures

are indelibly linked to the vision of one man, Robert Moses,

to transform Flushing Meadow into the last word on urban park

development. But so long as the Mets continue to play

in Flushing Meadow, even if in a new stadium built one day on

the other side of the parking lots, that part of the Robert Moses'

vision will continue to endure.

* * *

|