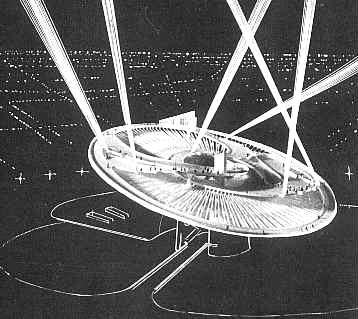

An artist's rendering of the original concept for Unisphere. According to the February 15, 1961 edition of the Herald Tribune:

- Widest of the structural elements will be the equator. Somewhat narrower will be the strips representing the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. Still others will from lines of longitude and latitude. They will be fixed to the sphere but appeare to be independent of it. A light representing a satellite, will move speedily along each orbit at different speeds and in opposite directions.

- Unisphere's base will be in the center of a 12-sided pool. One suggestion under consideration is that sculptures at the twelve corners of the pool represent the signs of the zodiac. These too would be in stainless steel.

- The concept is that verticle fountains will form a wall of water around the base of the sphere. Other fountains, at the edge of the pool, will arch inward. The fountains will be lighted from above and below.

|

|

Source: "Remembering the Future," "Something for Everyone: Robert Moses and the Fair" by Marc H. Miller, published to accompany the 1989 Queens Museum exhibition "Remembering the Future: The New York World's Fair from 1939 to 1964."

| The visual theme center for [Robert] Moses's Fair was the Unisphere, a 140-foot high, 900,000-pound steel armillary sphere covered with the representations of the continents and encircled by three giant rings denoting the first man-made satellites that had recently launched the space age. The emblematic Unisphere was to serve the 1964/65 Fair as the Trylon and Perisphere had served its 1939 predecessor - as the centerpiece of the fairgrounds and as a visual logo for Fair publicity. Occupying the central spot in Flushing Meadow Park, where the Trylon and Perisphere once stood, the Unisphere was the creation of Gilmore Clark, a longtime collaborator on the Flushing Meadow Park ground plan and the 1939 Fair.

The Unisphere's history was not without incident. One of Moses' first and most difficult tasks on assuming control of the Fair Corporation had been to come up with a visual logo to rival the highly successful Trylon and Perisphere. At first he hoped for an appropriate plan from the design committee, which included both Wallace Harrison and Henry Dreyfuss, the architect and designer who had created the Trylon and Perisphere and its interior exhibit, "Democracity." [Failing that,] Moses turned to Walter Dorwin Teague, the noted industrial designer who had served on the design committe of 1939, to submit a theme center idea. Moses's views on an appropriate central symbol are set forth in an August 21, 1960 memo to his assistant, Stuart Constable:

| It gets down to these alternatives. |

| A. |

Pure abstraction. Absolutely nothing doing. Toss it out. |

| B. |

Understandable abstraction symbolizing theme, with some significance or meaning for the average person. |

| C. |

U.N. buildings. Kind of corny. Unoriginal. U.N. probably won't like it. Neither will some of our people, but its not impossible. |

| D. |

Something from electronic or invention world. |

| E. |

Throgs Neck or Narrows suspension bridge. |

| F. |

Onward and upward symbol - Heaven knows what. |

| G. |

Something else. |

Teague's proposal, "Journey to the Stars," was for a 170-foot-high steel and aluminum spiral with helium-filled star-shaped balloons floating above. The spiral was animated by moving lights. In its most abitious stage, a ride took people to the top. A related two-dimensional design was temporarily used as the Fair's logo, but in an August 12, 1960 letter to Gilmore Clarke, Moses expressed his disappointment with Teague's concept. "At the risk of being put down as a barbarian, I think it is a cross between a part of a make and break engine and a bed spring, or should I say between a Malayan Tapir and a window shutter."

"Journey to the Stars" as envisioned by the design team at Walter Dorwin Teague Associates.

|

|

|

Two-dimensional design of "Journey to the Stars" that was temporarily used as the Fair's logo.

|

|

|

"The Galaxon" - another proposed Theme Symbol of the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair.

|

|

Another proposal Moses rejected was "The Galaxon," designed by Paul Rudolph, an innovated young architect and dean of the Yale University Department of Architecture. The 160-foot high 340-foot in diameter, saucer-shaped concrete structure, sponsored by Portland Cement, featured stations for star viewing, and was tilted at an 18-degree angle to offer an optimum view of the heavens.

Like the Teague and Rudolph proposals, Clarke's giant globe, encircled by rings, celebrated the space age that had begun with the Russian launching of Sputnik in 1957 and continued in America after John F. Kennedy's election as president in 1960. The Unisphere was clearly the type of "understandable" structure "with some significance or meaning for the average person" that Moses had favored in his theme center memorandum. As the world's largest global structure, the Unisphere also appealed to Moses's love of gargantuan scale. Since building the structure required the aid of newly invented high-speed computers to work out complicated technological problems, it also appealed to the engineer in him.

|

|

Comments by Robert Moses

Robert Moses - President New York World's Fair 1964-1965 Corporation

|

|

Source: Pamphlet: United States Steel Unisphere Ceremonies, March 6, 1963

| We looked high and low for a challenging symbol for the New York World's Fair of 1964 and 1965. It had to be of the space age; it had to reflect the interdependence of man on the planet Earth, and it had to emphasize man's achievements and aspirations. It had to be the cynosure of all visitors, dominating Flushing Meadow, and built to remain as a permanent feature of the park, reminding succeeding generations of a pageant of surpassing interest and significance.

And so we discarded startling abstractions and decided on a transparent, or shall I say diaphanous globe with orbits, with the contients outined, and ingenious lighting and other effects in place of revolving machinery.

This symbol floating over the meadow is going around the world. It signifies the New York Fair everywhere. Its effect is instantaneous. It speaks volumes in a single picture.

|

Source: Booklet: The Saga of Flusing Meadow, April 11, 1966

| We were deluged with theme symbols - mostly abstract, aspirational, spiral, uplifting, flashing, or burning with a hard and gemlike flame, whose resembalance to anything living or dead was purely coincidental. I can comprehend the magnificent symbolism of a four-footed musical theme like that of Beethoven's Fifth but the symbolism proposed by the avant-garde at Flushing Meadow, even if it be ambrosia to the inteligentsia, was surely caviar to the general.

Our U.S. Steel Armillary Sphere, the Unisphere, was derided by sour critics. They even said our wonderful fountains and magnificent night lighting were corny and we were accused of being crude, dull, defeated, uncouth Boeotians, lewd fellows of the baser sort.

|

|

|

Artist John C. Wenrich rendering of the final design for Unisphere

|

|

|